Hamlet’s Dilemma from Ray’s Calcutta

A review of Satyajit Ray’s movie “Kapurush” by Prabhas Lahiri

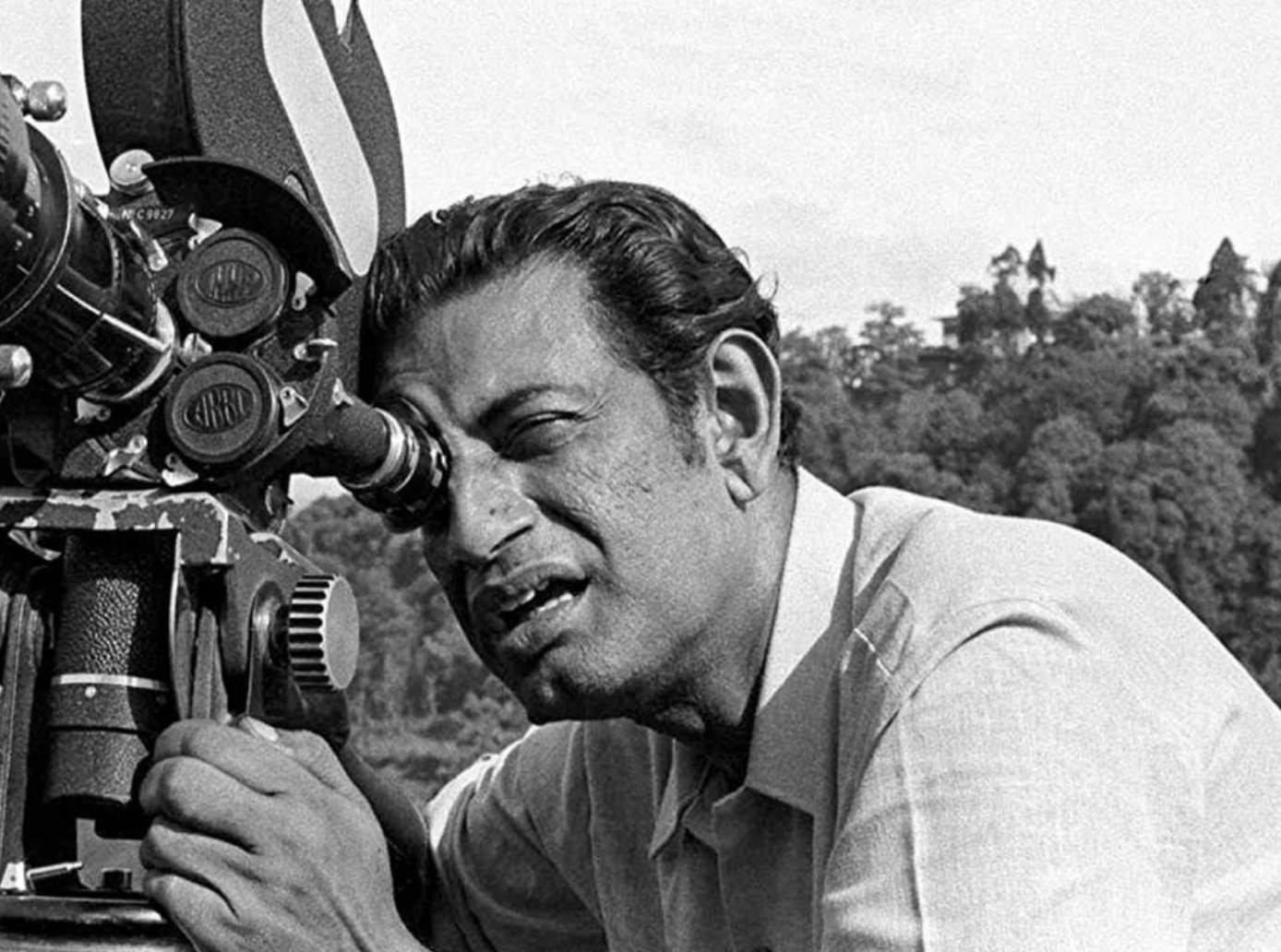

Satyajit Ray was born in 1921, in Calcutta, British India, in a distinguished cerebral family, as he grew up he quietly turned himself probably into a most humane and tolerant film maker in the world. He directed his first motion picture Pather Panchali (song of the little road) at 34 and won the inaugural Best Human Document award at Cannes Film Festival in 1956. Later he went on to earn a Golden Lion, a Golden Bear, two Silver Bears, innumerable National Awards, an honorary doctorate from Oxford University – only the second after Charles Chaplin and an Academy Honorary Award in 1992. Indiscreetly speaking, Ray is considered equal to 1950s-1960s great filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman from Sweden, Akira Kurosawa from Japan and Vittorio De Sica of Italy. Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) is possibly the only polymath in the world of cinema who ultimately wrote the story, developed it to a script, composed the music, put the lyrics in the lips, looked through the lens, co-edited the film, did the casting, illustrated the credit titles and even produced the publicity material. Each time one sees a Ray’s film one finds the director holding a mirror before the audience, ‘Know thyself’ the ancient Greek aphorism. His work is relevant even today because he stuck to the core values latent in human being. He likely could witness human mind from all its perspectives that ultimately culminated in an innate sense of compassion even in the unworthy.

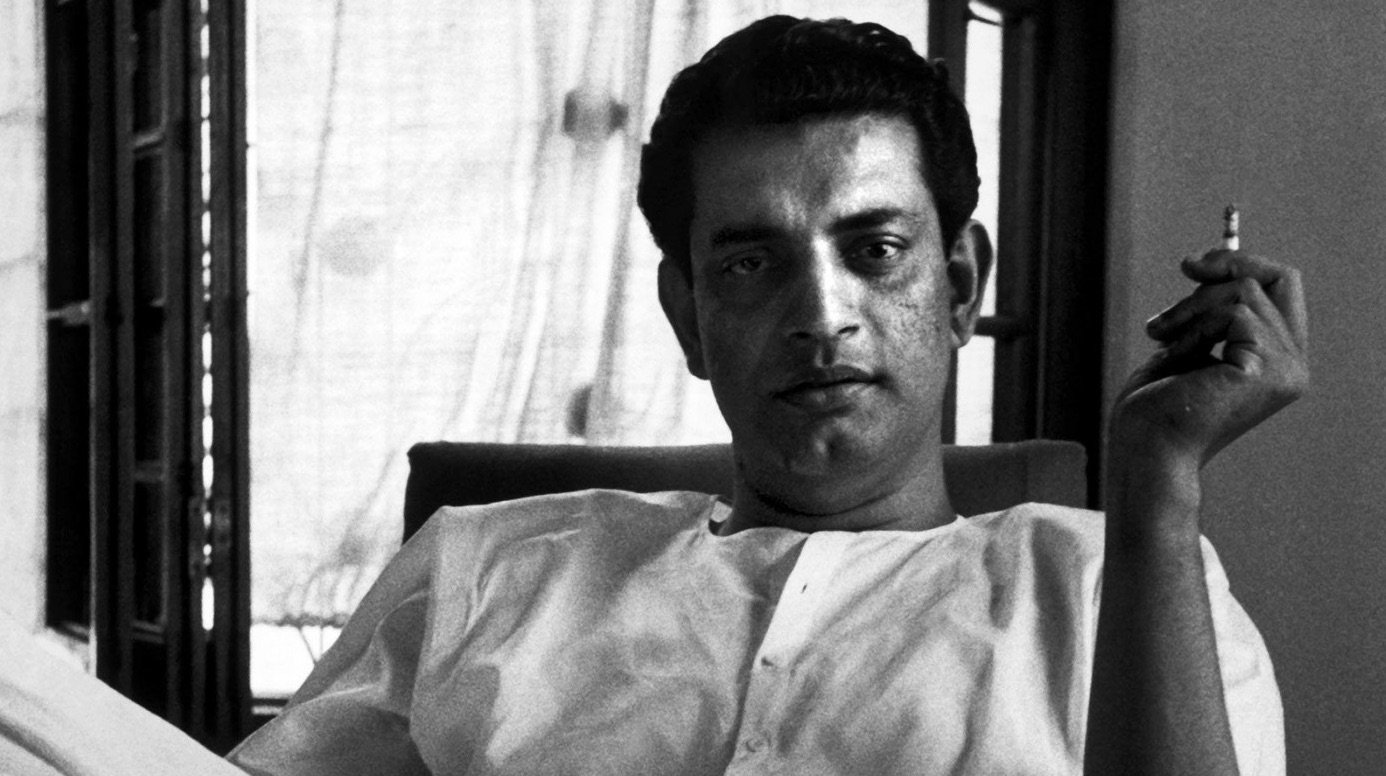

Hamlet is one such paramount character of enormous complexity of utter desolation, brackishness and cynicism arising from Shakespeare’s play. Hamlet suffered from indecisiveness, hesitancy and contradictions. Many analytical brains for centuries have been impatient in deciphering and analyzing it but none have dared to live the life of it. Only a few actors of indisputable repute like John Gielgud, Orson Welles, Laurence Olivier and Richard Burton had only tried the role of Hamlet in their lifetime. It is not known whether Ray had any plans to decipher Hamlet but it is for sure that Ray’s favorite and legendary actor Soumitra Chatterjee wanted to do it.

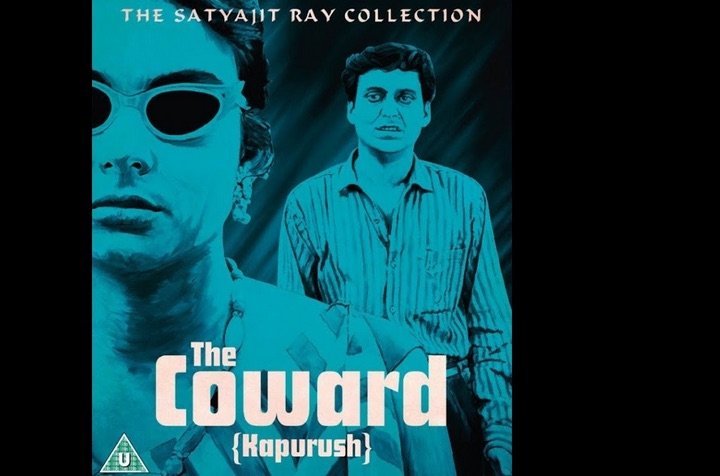

It is a pity that ‘Kapurush’, ‘The coward’, is Ray’s less talked about movie and I know not in entirety as to why it failed to make an impact at the Venice film festival in 1965. It is a drama film where the protagonist Amitabha is played by Ray’s all time favorite actor Soumitra Chatterjee opposite the actress Madhabi Mukerjee, who also was seen in Ray’s Charulata and Mahanagar. The plot is based on Premendra Mitra’s short story ‘Janaiko kapurusher kahini’, which literally translates into ‘The Story of a Certain Coward’. The story is an unremarkably simple one, dealing with the fate of two lovers, who love each other but never could make it to a marriage. And the accident in the story is equally elementary when the two meet each other later after the girl had been married off to another man Bimal Gupta, a tea-planter, played by Haradhan Bandopadhayay.

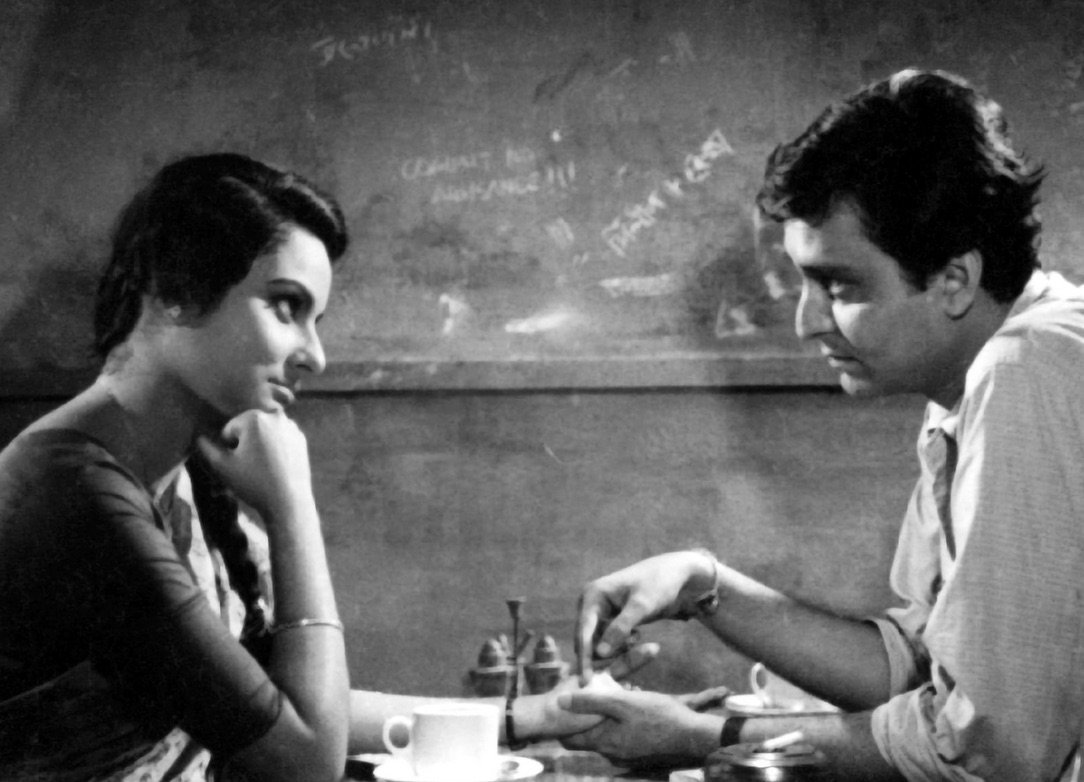

Ray’s storyline differs quite substantially from Mitra’s book in the sense that the backdrop of the movie is different which portrays some kind of a sophistication of an educated class, in which post marriage Ray’s actress puts herself in a cocoon shedding her childish sexual undertones. Whereas, Mitra in his story paints Karuna with adult sexual connotation, thus she is desperate to leave her married life for a life with Amitabha. Ray didn’t alter Amitabha’s character making it an essential and a pivotal one. This kind of a major change, which Ray had done in his other films as well, lays the foundation for Ray’s human analysis, scene by scene in an austere and conservative convention. It is at par with that of other notable filmmakers of that time. The magic is in the treatment of the celluloid by Ray and how he glorifies every character with lucidity and candor. Still it conforms to Ray’s taste for minimalism.

Though Ray is a good weaver of the story, he had his help from a very able and skilled editor Dulal Dutta. One gets the feeling of reading a book page by page when one watches Ray’s film, similarly to the feeling of watching a film while reading the book ‘Tintin’ by Belgian Georges Remi who wrote under the pen name Herge. If one watches Kapurush very carefully a viewer will often be gifted ‘Double Entrendes’ by Ray through his script. It adds to the literary value of Ray’s films.

Even till the end of twentieth century, marriage had been the only sacrosanct “license” an Indian society would offer to lovers to incorporate themselves lifelong into a relationship in the society without others raising their eyebrows. Even holding hands in public was not permitted during those times. Staying together without getting married was a taboo and some kind of an anathema. Much of it has changed now. For a viewer from another country where marriage is optional, this should be borne in mind and appreciated with compassion before viewing Kapurush. Or else much of the tenderness and clemency from the part of the viewer will be lost.

Most of the film’s background scenario rests on a small town in the foothills of the Himalayas at a tea garden, except for one or two flashbacks into the two lover’s growth in the metropolis of Calcutta.

Music had always been Ray’s passion, which stayed entwined with his yearning and appetite for moving pictures and he firmly believed that it delivers harmony to the whole film. The very eerie, foreboding title music in Kapurush holds the disquiet and agony Ray had wanted to deliver directly into the heart of the viewers and sets the pace for this movie. It even behaves as a rhythmic ostinato holding and moving the events in the movie. In Kapurush music, Ray has seamlessly moved from its western classical style to the Indian one especially when reversing from a present day scenario into a flashback in the story. His use of Beethoven too is understated but profound, and using two compositions of Rabindranath Tagore’s, a literary Nobel winner of the last century, Ray has meticulously portrayed Karuna’s post-marital temperament and identity.

In Andrew Robinson’s book ‘The Inner Eye’, Ray had conveyed to Robinson that the film expresses some kind of cowardice and selfishness. But whether a Hamlet existed in Amitabha Roy was not known. It is likely that Ray had unknowingly developed a Hamlet in ‘Kapurush’. The protagonist Amitabha Roy apparently suffers from indecision in Kapurush. In spite of Karuna’s optimistic statement that they both together can survive a happily married life, Amitabha proves himself to be slippery towards any commitment. He brings in a multitude of excuses to delay their marriage. To the modern psychiatrists, Hamlet suffered from some acute depressive illness with some obsessional features. It brings in hesitation to act promptly. It is some kind of a character defect, which has the ability to terminate itself into tragic outcomes. In Hamlet a delay from the protagonist’s end to take revenge results in seven unnecessary deaths and lots of blood letting at the end, whereas in Kapurush, it results in torment in one and sleepless nights in the other, but no one dies in the end.

It appears true that Amitabha was not feigning a person suffering from indecision or he is a malingerer of some sort, as Harvard University through one of it’s lectures by Wilson and Fradella draws that ‘The Hamlet Syndrome’ confirms partly to feigning madness or ‘failed insanity’ defense. But it is well appreciated now that long standing depression leads to indecision. Amitabha suffers from insecurity and in his unconscious world it brings in some cognitive defects. He is emotionally devastated and at one point of his journey he conveys to married Karuna that he has earned a comfortable life out of his present vocation, which still is meaningless to him. Such depressive thoughts had earlier come to Amitabha, which a viewer may miss if one loses his attention while watching Kapurush. Depression can drive such statements out from its sufferer’s mouth. Hamlet did suffer from depression, resulting in failures to make firm resolves, as confirmed by some modern day psychiatrists.

As a reviewer, I feel that it is not a story of a love triangle as has been portrayed since the early days of this movie. Karuna’s husband Mr. Gupta,the tea-planter, is no match for the heroic looks of Amitabha. When the three characters come face to face with each other, the protagonist is probably not in love with his confidant – Karuna. The story literally builds itself upon the ‘faults in decision making’ Amitabha had sown in Calcutta. Ray builds it in a step by step manner, never hurriedly and not displaying it’s scaffolding. He confidently stores and hides a tight slap on theviewer’s imagination, which thaws the audience at the end of themovie. It is a straight and a simple case of Hamletian dilemma wheretragedy is often the only outcome to embrace.

Since the inception of this film, in comparison to the words spoken by Mr. Gupta, a fabulous but seemingly voluble host who had rather boldly and brazenly declared himself a lonely individual, Ray has told a rather emotional script through the protagonist. However, one should not be fooled by Mr. Gupta, who might have a full insight into the past and future of the coward. Ray has deftly and delicately obscured this fact as a tool for our imagination. In a blatant contrast, Karuna’s utterances and declarations are curt,concise and matured. This pronounces the effect of ‘Hamletian Dilemma’ in Kapurush or the coward. But one must appreciate and not forget Ray’s symbolicassertions in the form of a passing fire brigade and a game ofpatience.

The film will lose its value when watched as a large canvas if one misses the use of bold diagonal stripes Ray had adopted in the costume to imply a disruptive but energetic movement, while on the other end narrow, near coalesced vertical stripes to confer a dramatic but not disruptive character with fluidity in the protagonist.

Kapurush, from Ray’s only double-bill is a slow but steady portray of complex relationships in the background of Calcutta’s own Hamlet in a turbulent post independence period. It is undoubtedly a period drama that should never be missed.

By Prabhas Lahiri, Calcutta, India